Aug. 11, 2021

Mobile outreach team provides compassionate medical care to underserved Calgarians

For Calgarians experiencing homelessness, poverty or addiction, navigating healthcare services can be overwhelming.

An innovative collaboration between community paramedics and specialized outreach workers is reducing barriers to care faced by vulnerable, underserved and hard to reach Calgarians by delivering services in the community.

Proactively reaching out to those struggling with mental health challenges can prevent people from falling through the cracks of the health-care system, says Dr. Bonnie Larson, MD, physician lead of the Street CCRED collaborative at the O’Brien Institute for Public Health, Cumming School of Medicine, one of the program partners.

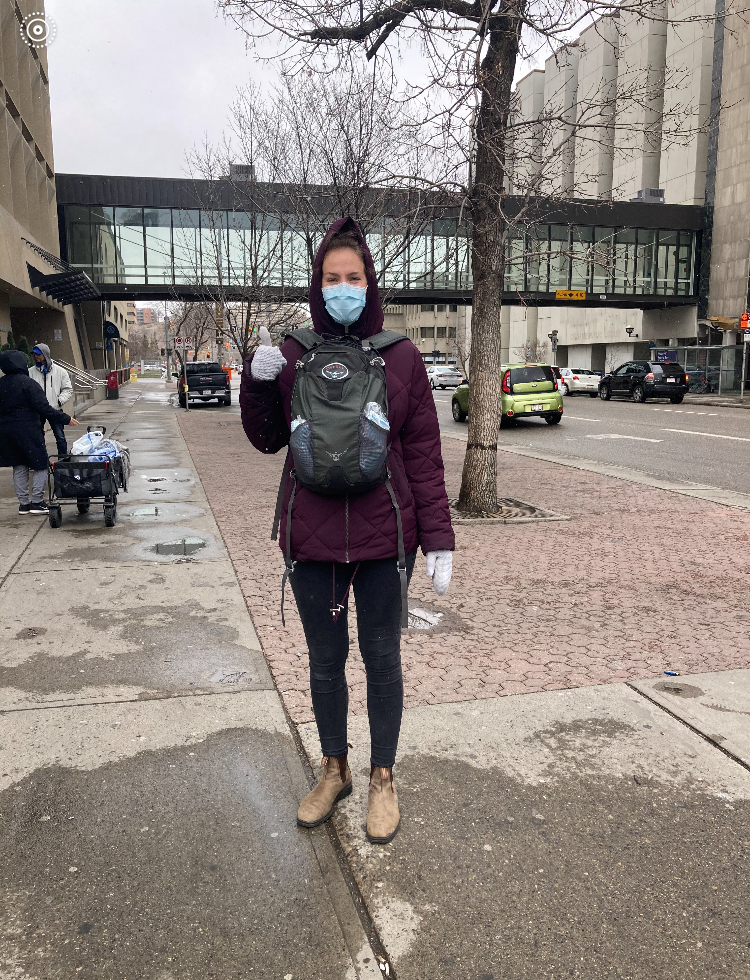

Registered social worker Marleen Dorrestijn provides mental health and social supports to at-risk communities with the Alberta Health Services Mobile Integrated Healthcare team.

“We’re trying to reach people who often have the greatest health-care needs and meet them exactly where they are — whether that's under a bridge, in a shelter or back alley — in order to close the health equity gap that exists in our society,” she says.

After a successful pilot run, the collaboration – made up of Alberta Health Services (AHS) Mobile Integrated Healthcare, in partnership with Street CCRED and Calgary Health Foundation – recently received operational funding through Calgary’s Mental Health and Addiction Strategy Investment Framework.

The outreach team is made up of City Centre Team (CCT) Community Paramedics — an existing AHS service dedicated to addressing the unique health needs of those living with homelessness, substance use disorders, and complex health needs — and outreach workers with expertise on the unique needs of at-risk communities.

“The existing CCT Community Paramedic program was already extremely effective and by layering an additional level of support with outreach workers, who have a deep understanding of health systems and available social supports, they’re able to do even more,” says Larson.

Calgary has a wide range of programs and services available to address people’s mental health needs, however, navigating services without support can often be intimidating, overwhelming, and may lead to further harm due to the fragmentation in the system, says Larson.

The outreach workers are able to identify and provide supports for needs that would have otherwise gone unmet, such as accessing financial aid, housing and other social supports, says Marleen Dorrestijn, an outreach worker with the program.

“Making an effort to meet someone in their environment and take the time to build a relationship can help people who have probably been discriminated against, or mistreated by, the health care system feel safe,” says Dorrestijn, a registered social worker.

Mobility is one of the program’s biggest assets, agrees Michele Smith, manager, AHS Mobile Integrated Healthcare.

“Research supports that healthcare is most effective when you feel safe and comfortable, and that goes for people who have a stable dwelling as well as those who are sleeping rough, insecurely housed or accessing the shelter system,” she says.

Mobile health care is also an effective way to take strain off of the acute care system, which is especially important during a pandemic, says Smith.

“The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the importance of expanding healthcare delivery beyond traditional models, and of tailoring interventions to address inequity and improve health outcomes,” she says.

Crisis response in the community

The Mobile Integrated Healthcare collaboration is funded in part through the Community Safety Investment Framework Fund, a collaboration between Calgary Police Service, the City of Calgary and community partners to support Calgarians in crisis due to mental health, substance use or other similar challenges.

The $16 million fund reallocates a portion of the City of Calgary fiscal reserve and the Calgary Police Service budget to strengthen existing community crisis response programs.

“In the ongoing context of anti-racism and reconciliation, this is the right time to have discussions and make decisions about where we allocate our resources,” says Larson.

"The police are always there to work with us when we need them, but often a mental health crisis in the community can be managed more effectively with an appropriate health and social services response,” she says.

Bonnie Larson is a clinical assistant professor in the Department of Family Medicine and a member of the O’Brien Institute for Public Health at the Cumming School of Medicine