June 21, 2023

Research study ‘feels like hope’ for Calgary family

Linden Walsh experienced her first seizure when she was six months old. She had been developing typically; no one suspected she had a rare genetic mutation. Diagnosed with Dravet Syndrome, 14-year-old Linden lives with unrelenting seizures that are treatment resistant.

Deepika Dogra explains how organoids are created and grown in the Kurrasch lab.

Riley Brandt, University of Calgary

“Linden lives in a very controlled environment because of her seizures and cognitive impairment,” says Erin Walsh, Linden’s mom. “Someone is with her 24/7. She is not stable on her feet.”

Dravet Syndrome is a rare form of epilepsy that is often diagnosed early in life. Children appear to be developing typically until suddenly seizures begin, which if are not controlled, can lead to developmental delays. The work of Dr. Deepika Dogra, PhD, an emerging leader at the Hotchkiss Brain Institute (HBI) in the Cumming School of Medicine at the University of Calgary, is creating hope for Linden and her family.

Dogra collects blood from Linden and tricks her blood cells into becoming a cell type capable of giving rise to neurons. She then grows these cells into brain-like structures called organoids.

“The cerebral organoid is a cultured neural structure that allows me to test various drugs to see which one or which combination will work for a specific person,” says Dogra, a postdoctoral fellow. “This method also helps us eliminate possibilities, so a child doesn’t have to keep trying new medications.”

Researcher holds petri dish containing cerebral organoid grown from Linden’s blood.

Riley Brandt, University of Calgary

It’s the type of work that could benefit from a US$12.5 million injection of funding from the late American philanthropist and energy industry giant T. Boone Pickens. The gift is bringing new opportunities for brain and mental health research at the HBI.

“We can screen 450 drugs in just a few months in a brain organoid established from Linden’s blood. Currently, an individual with Dravet Syndrome could maybe try four to six new drugs in a year,” says Dr. Deborah Kurrasch, PhD, professor at the Cumming School of Medicine and principal investigator leading the organoid research project.

“Brain organoids are the new player on the scene. We hope this technology will enable us to help Linden’s medical team and family identify the best treatment to control her seizures and on a reduced timeline.”

New frontier for precision medicine

Kurrasch says the technique of growing brain organoids really took off around 2016. The field started to realize this approach could be a human-based alternative model system to research traditionally conducted in mice, rats, and even zebrafish, for conditions like epilepsy.

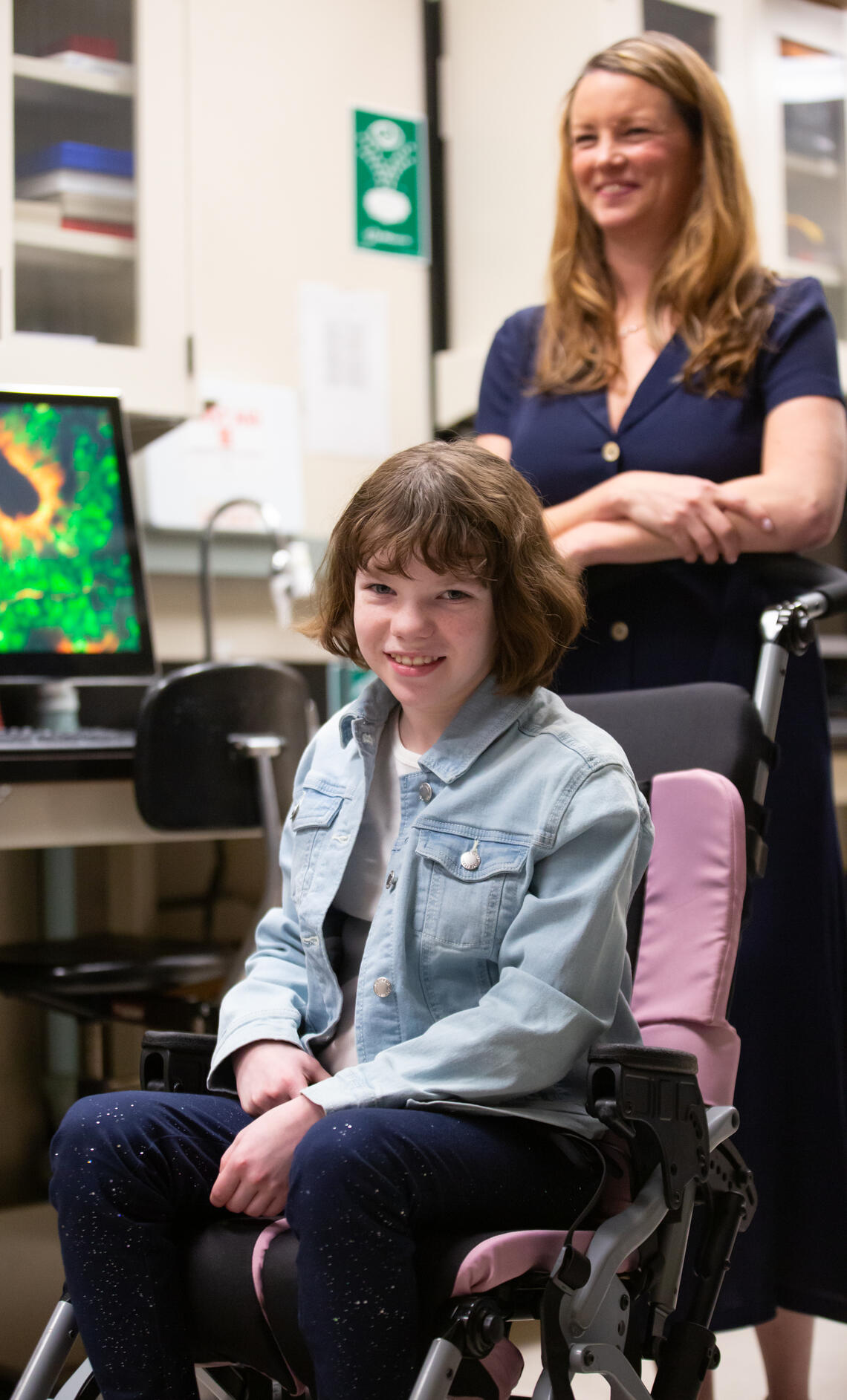

Linden and Erin Walsh.

Riley Brandt, University of Calgary

Kurrasch says there is still a lot to learn and discover about growing organoids. Researchers are studying various growth chambers, proper balance of nutrients, even optimal oxygen levels all to identify the parameters that best mimic the human brain environment

“These cells rely on cues from their microenvironment to develop properly,” says Kurrasch. “Some cells will become a neuron while others will develop into another cell type found in our brains, and the microenvironment helps drive these decisions. The more accurately we can mimic this environment, the more reliable these brain organoids will be as a model system for drug testing and disease modelling.”

For the Walsh family, it’s the first time that Linden’s specific mutation has been looked at.

“It feels like hope. Linden’s seizures are extremely limiting. She is never alone, even at night, one of us sleeps with her,” says Walsh. “We don’t want to be unrealistic. We understand this type of research is new. We’re very grateful to have access to it.”

Brain and Mental Health Strategy (BMH)

Led by the Hotchkiss Brain Institute at the University of Calgary, the BMH Strategy explores an improved understanding of the brain and nervous system and new treatments for neurological and mental health disorders, aimed at improving quality of life and patient care. Learn more about the HBI.

Child Health and Wellness

The University of Calgary is driving science and innovation to transform the health and well-being of children and families. Led by the Alberta Children’s Hospital Research Institute, top scientists across the campus are partnering with Alberta Health Services, the Alberta Children’s Hospital Foundation, and our community to create a better future for children through research.

Deborah Kurrasch is a professor in the departments of Medical Genetics and Biochemistry & Molecular Biology at the Cumming School of Medicine (CSM) and a member of the Hotchkiss Brain Institute, Alberta Children’s Hospital Institute, and Owerko Centre at the CSM.