Ryan Flinkfelt in the opening sequence of his co-made video on ski resorts and climate change.

Ryan Flinkfelt and Megan Canuel

Feb. 22, 2018

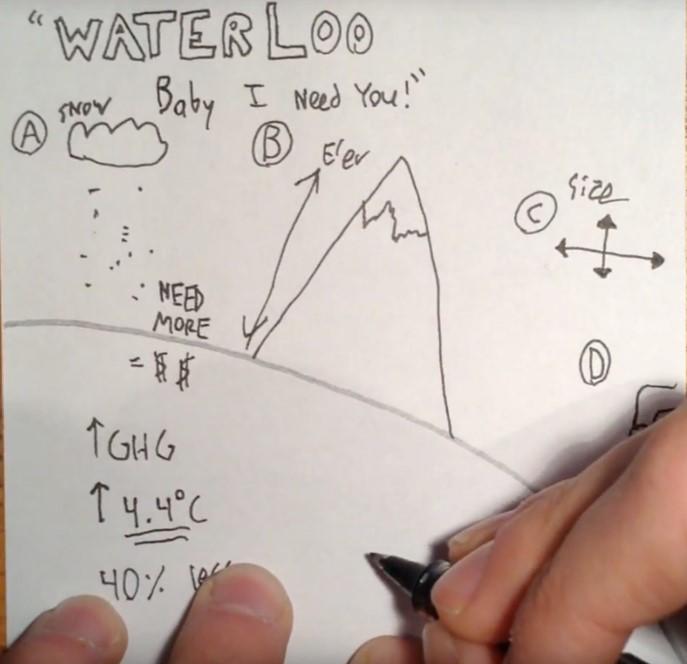

Ryan Flinkfelt in the opening sequence of his co-made video on ski resorts and climate change.

Ryan Flinkfelt and Megan Canuel

You want to take an abstract, complex, all-encompassing subject like climate change and make it real for people? Turns out talking about the future of ski hills does the trick. Better yet, make a video.

That’s what undergraduate geology students Megan Canuel and Ryan Flinkfelt did as an assignment for their fall 2017 course — The Geologic Record of Global Change — taught by Annie Quinney, an instructor in the Department of Geoscience. And as the world gathers this week to celebrate snow and ice at Pyeongchang 2018, the reverberations of what they learned has stayed with all of them.

Quinney asked her class to find a peer-reviewed scientific paper discussing climate change and then to creatively communicate the results to a lay audience of their peers in a straightforward and meaningful way.

“The thing about climate science is it is so complicated, inaccessible, especially when you are trying to read these scientific publications,” Quinney says. “The task for students was to distil a paper into something that was meaningful to everybody.”

First, make a meme

The first part of the project was to create a social media campaign — a blog post, meme, or Twitter feed — anything, Quinney says, that would capture the interest of the general public. Part two of the assignment asked students to delve deeper into the paper’s content, again with the freedom to communicate findings in any way they felt would be effective.

“I think they had a genuinely good time doing the work, I got amazing stuff back, and the projects they produced were spectacular,” Quinney says. “Some students chose to do podcasts, games, and YouTube videos.”

Many students chose research papers on the future of ski hills. Canuel and Flinkfelt’s research paper was "Climate Change Analogue Analysis of Ski Tourism in the Northeastern USA " out of the University of Waterloo.

They turned the nine-page research paper into a much more digestible seven-minute video that highlights the key learnings. Specifically, evidence suggests ski seasons will shorten, higher-altitude and -latitude resorts will fare better than those at lower altitudes and latitudes, and only resorts that are neither too big nor too small will survive because of the costs of snowmaking.

In their explainer video, Flinkfelt illustrates as Canuel’s voiced script summarizes concepts.

Ryan Flinkfelt and Megan Canuel

Cascading effects

The students also highlighted making snow isn’t an easy answer for all powderless ski hills because snow requires a significant, accessible source of water.

"We called the resorts that will survive 'Goldilocks resorts,'" Canuel says. “Too big, and snowmaking and maintenance will be too expensive. Too small, and they won’t have the budget and customer base to survive.” As well, the resorts that do make it will be busier, meaning the ski hill experience will change for everyone.

“I think people expect climate change to look like it does in movies like 2012 or San Andreas, with huge earthquakes, fires, and natural disasters,” Flinkfelt says. “But climate change is more gradual than that, even though over time there will be huge impacts on so many aspects of our lives.”

As she reviewed the class assignments, Quinney was also struck by the endless ripple effects of climate change. “Some students talked about bees, others about change in the spread of disease, or ski resorts and water. When you start to look at how many things are interconnected, you realize everything has a cascading effect.”

“It was an eye-opener,” Canuel says. “We have learned a lot about the past as geology students — like, 4.5 billion years of past earth history — so this course was kind of something about the present, which was super interesting.”